The question that keeps appearing before me is about what changing keys does to your memory. I’d like to build a framework to seek a more particular answer.

long-term and medium-term tonal memory: ii vs. V/V

To begin down this path, I’m going to start with the vi-ii-V-I sequence I’ve been going on about in the previous posts.

I’d like to contrast vi-ii-V-I with a vi-V/V-V-I sequence, which is only one note away, but makes a real difference in perceived brightness and in orientation.

Here they are to compare as audio files. First, a clean vi-ii-V-I:

Then, something similar, but with V/V instead of ii (the second chord is brighter):

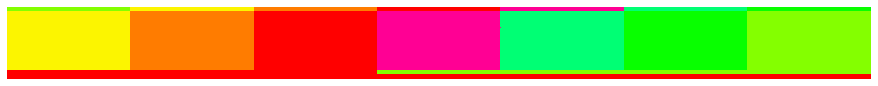

The analysis here shows the V/V changing something in the medium-term memory below the yellow box (look closely for the orange stripe below the yellow). It also does not disrupt the longest-term memory (consistently red, C Major, at the very bottom).

memory of major in relative minor

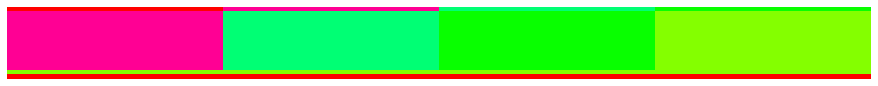

The relative minor is also one parameter away, and we can see that as relative minor, it also contains a memory of C Major (red) in the long-term memory, though the medium-term memory settles in around D minor:

This is a preliminary change in tonality: something that leaves a near-audible trace in the medium term memory. The change could be as short as a V/V, or could settle into a related key.

Here it settles into A minor, which is where the major sequence starts — put them together and you have something like ‘Autumn Leaves’, plus a bit of a new image of how Autumn Leaves descends in harmony as well as melody.

song structure: Autumn Leaves

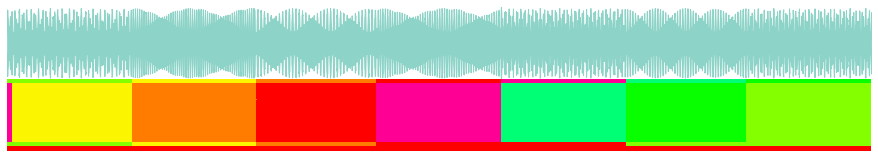

So here are the first seven chords of Autumn Leaves analysed as audio:

And here as analysed from within the system’s clean taxonomy.

There are some minor differences in the long-term memory of these two versions, which is fantastic. The audio analysis shows that the music must find its way from a ‘real’, unprepared entry point; the prescribed, systematic version, knows exactly that it is in C Major. Our ears are somewhere in between, or around, these two possibilities.

This flexibility, which allows the same music to be analysed in multiple ways simultaneously (by different ears or different lines of thought), is what allows for flexibility in other musical parameters: dynamics, ornaments, tension.

Thus, two chords or sequences can sound exactly the same, but longer-term memory can always indicate other possibilities for memory and prediction.

It might be called ‘room for interpretation’ – though interpretation a wider field. But above all it indicates an irreducible volatility, full of potential, at the bottom-most level of computational analysis.

Somewhere, far above this analysis, lurks Cannonball Adderley. And the guys playing Autumn Leaves on street corners, giving ears and lives a bit of flow as they go.