By 1817, when he was 20 years old, Franz Schubert had written hundreds of works. Although his official opus numbers were still in the single digits, the number of works he had already written was incredible. Many of these works were published later. Schubert was as good as he was prolific. The majority of these works were songs, written for (and with) friends. Franz von Schober, a friend since youth, and Johann Michael Vogl, an established singer on the Viennese scene, were especially present around this time. Schober (among others) would write poems, Schubert would set them, and Vogl would sing and promote them.

Songs were at the center. Most of Schubert’s instrumental works were yet to come. So in approaching an instrumental work from Schubert during this time, one might be tempted to ask what the words might be, if there were any. It’s a foolish question, and not one for which one should seek a direct answer. But it does bring fruitful thoughts with it: “What direction do moods and associations take?” for example, or, “How are words and music related in Schubert — or anywhere else?” From these questions, things can take shape. It’s worth pointing out, in this line of thinking, that the song-texts for Schubert were not in themselves particularly stirring. They are like a dock in a lake: something from which one may spring into something else, something full of life and variance.

The music of the A Major Sonata does have this strange light depth, of the feeling around words. A sense that from casual, friendly things something transporting may suddenly occur, leaving you where you were before, but lighter. There is the sudden change of a walk into a wander, the confusion of mood and weather, leaving a listener unsure of what was private and what was public. The experience of listening with a crowd becomes strangely private with Schubert — more so than usual.

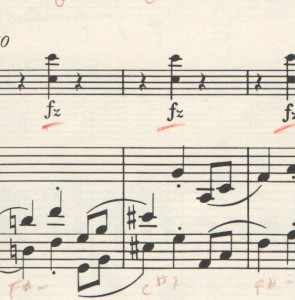

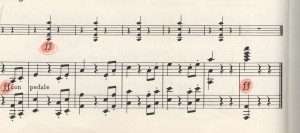

This all happens in a surprisingly sophisticated technical way. There is something naïve about Schubert’s technical means, but one should be so lucky to be so naïve… without too much mincing around about particulars, it is worth pointing out, for example, the relationship between an outburst in the Scherzo (2nd movement):

and the end of the 4th movement:

There is a mnemonic tightness, a sense of meaningful similarities that brings things together. This tendency will develop enormously for Schubert over his next ten years.

Last, by way of re-introducing words, and our festival in its 15th year, here are the words for Schubert’s An die Musik, written by Schubert’s friend von Schober, set by Schubert in the year of the A Major Sonata, 1817. They are an appropriate touchstone, if not the heart of the matter:

Du holde Kunst, in wieviel grauen Stunden,

Wo mich des Lebens wilder Kreis umstrickt,

Hast du mein Herz zu warmer Lieb’ entzunden,

Hast mich in eine beßre Welt entrückt,

In eine beßre Welt entrückt!

Oft hat ein Seufzer, deiner Harf ’ entflossen,

Ein süßer, heiliger Akkord von dir

Den Himmel beßrer Zeiten mir erschlossen,

Du holde Kunst, ich danke dir dafür!

Du holde Kunst, ich danke dir!

—

You lovely art, in how many grey hours,

When life’s mad whirl beset me,

Have you kindled my heart to warm love,

Have you transported me into a better world,

Transported into a better world!

Often has a sigh flowing out from your harp,

A sweet, divine harmony from you

Unlocked to me the heaven of better times

You lovely art, I thank you for that!

You lovely art, I thank you!