The string trio is an unforgiving group to write for. Its power and dynamic range are limited to that of only three instruments. Its three-note textures leave little room for doubling or for flexibility of voice-leading. Moreover, the violin, viola, and cello are all fairly similar in their materials, purpose, and expressive range. LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN, though, seemed to have no trouble with any of this. Beethoven’s concentrated style of writing was well suited to working powerfully with limited resources.

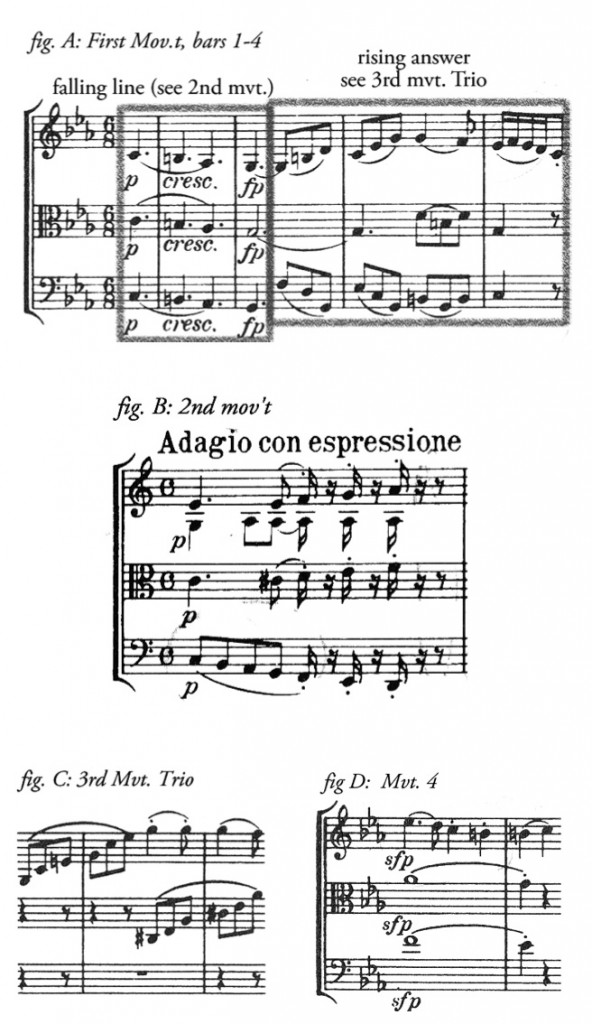

From the first bars of the trio, there can be no doubt of its author. Beethoven roars in as the author with whom we are well familiar, introducing a simple, insistent 4-note pattern over a falling harmonic-minor line (fig. A, bars 1-2). This entrance requires answers (which  come, at least partially, in bars 3-4). The second movement returns to the falling scale line, but releases it to fall further (in the cello), while the violin makes an offering of a four- note rise (fig. B). The third movement also carries this four-note rhythm, but concerns itself also very much with the initial answer answer (fig. A, bars 3-4), especially in the trio section (fig. C). The last movement seems to have solved something about this falling figure – something to do with allowing it to find a cadence (fig. D).

come, at least partially, in bars 3-4). The second movement returns to the falling scale line, but releases it to fall further (in the cello), while the violin makes an offering of a four- note rise (fig. B). The third movement also carries this four-note rhythm, but concerns itself also very much with the initial answer answer (fig. A, bars 3-4), especially in the trio section (fig. C). The last movement seems to have solved something about this falling figure – something to do with allowing it to find a cadence (fig. D).

Beyond a few images of basic patterns, the music is difficult to describe – there is little to add that would not seem terribly abstract. But in the end the piece doesn’t seem abstract – it is indeed astonishingly visceral for such lean writing. One gets a sense of just how strongly grounded Beethoven was as a composer even at opus number nine. When he would later write for orchestra and chorus and soloist and expand into pre-Wagnerian greatness, it was never without the absolute knowledge of how to do something comparably powerful with only three stringed instruments.