The power and greatness of Beethoven’s compostions changed much as as he (in his mid-forties) grew toward a ‘late’ period. By 1815, there was little to be found of the public rallying in the ‘Eroica’ Symphony, and little of the spaciousness of the ‘Pastoral’ Symphony; there was also little of the pure energy of the Op. 18 String Quartets, or the bright, exploratory impulse of the Op. 59 string quartets. Instead, there were the moods of a man, functionally deaf, once a pianist, alone. In this late phase, Beethoven wrote perplexing and wonderful string quartets. He wrote his ninth symphony. He wrote a Missa Solemnis. And he wrote piano sonatas, exploring the strange topography of mind and soul at the piano. The piano sonatas are willful, complicated, abstract, simple, incomplete, heart-rending, awful, playful, and sublime. To have the kind of compositional power Beethoven owned throughout his career aimed inward by deafness is quite terrible to imagine. But he also was released from the normal gravitation of both musical conventions and public life.

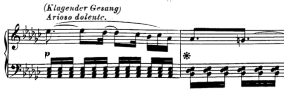

In his late period, though, he did gravitate toward ancient music, and found there much to center his thoughts around. Since Beethoven was writing his Missa Solemnis, he had probably been looking to Bach’s choral works for models, and in the piano sonata Op. 110 he includes a quotation (and a heavy one at that) of the aria ‘Es ist vollbracht’ (‘It is finished’) from the St. John Passion. There is nothing hidden about it, it is marked as an ‘arioso dolente’ (pictured), and preceded with an unmistakeable recitative cadence. The arioso is first followed by a strange, strict fugue (more ancient music…), and then reappears altered. It is again followed (after bell sounds) by the same fugue, but upside down and ‘nach und nach wieder auflebend’ (which indicates both ‘more lively’ and ‘again living’).

The message of this reflection on Bach, while hard to state explicitly, has clearly to do with his own sense of ‘late’-ness. That’s not all there is to the sonata, by any means: there’s much distance between the first two movements, which can be (knowingly) simplistic and brusque, and the clearly existential direction of the arioso-fuga area. And that distance is also central to the piece, though it is somewhat harder to name and describe. But thoughts on Bach are near the core of the sonata’s matters, providing focus (thankfully external) for a composer who is clearly, and intentionally, wandering wherever his willful will will take him.