We should begin to look at Mahler’s Fourth symphony from the end, because the end is what it’s about. Its fourth and final movement is the center of its weirdness, and it is also the source of a great deal of music which precedes it (including some music in other symphonies and songs). The fourth movement of the Fourth Symphony is itself a song, ‘Das Himmlische Leben’, whose narrator is a child in heaven, singing praises of daily life there:

We lead angelic lives,

yet have a merry time of it besides.

…

John lets the lambkin out,

and Herod the Butcher lies in wait for it.

…

Saint Luke slaughters the ox

without any thought or concern.

…

Should a fast day come along,

all the fishes at once come swimming with joy.

There goes Saint Peter running

with his net and his bait

to the heavenly pond.

Saint Martha must be the cook.

Strange things, these. An afterworld in which biblical metaphors (lambs of God, slaughterers of oxen, fishers of men) become gustatory matters, and matters whose violence seems invisible to the narrator. Perhaps the strangest, darkest reference is to Saint Ursula, who (as the story goes) was martyred alongside her 11,000 handmaidens around Cologne in 343:

There is just no music on earth

that can compare to ours.

Even the eleven thousand virgins

venture to dance,

and Saint Ursula herself has to laugh.

One is left to wonder what misfortune brought the young singer to heaven to see (and taste) all of this. But whatever his/her naïve misunderstandings may be, the song’s singer is right that the music in the air is something extraordinary. Let us take a look, then, at what music rains from cloud nine.

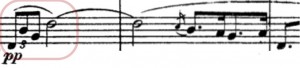

Perhaps the most efficient, if not the most atmospheric, place to look is to the three-beat pickup figure at the opening of the fourth movement. It is highlighted below:

The sound of this figure can be traced all the way back to the cellos in bar 8 of the first movement (40 minutes earlier — the last note is different, but the similarity is by the end of the phrase undeniable):

The climax of the third movement also contains a very complete and important prefiguration of the fourth movement’s opening, in the horns and trumpets:

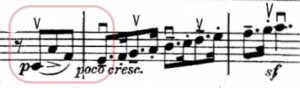

Searching back even further: in first movement, there is a wildly overmarked, yet somehow rather nonchalant three-note pickup which ushers in the first melody. So the violins at bar 4:

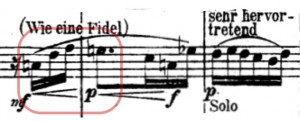

The second movement uses this three-note figure, too. (No description of the second movement is complete without mention that it is to a greater or lesser or degree a portrait of ‘Freund Hein’, a Germanic personification of death who plays a creepy violin.) On the strangely-tuned ‘fiddle’ there is a distended version of it with funky dynamic motion:

Finally: there is a strange, sequential, and clearly metaphysical transformation during of the third movement, which takes the first movement’s initial, nonchalant scale motion to higher and higher conclusions.

The final bars of the third movement are marked ‘Gänzlich ersterbend’ (‘completely dying away’). In this way the content of the fourth movement is slowly uncovered in the previous three. One reaches heaven by dying, driven by three-note pickup.

Mahler’s fourth is a long symphony — his shortest in time and smallest in forces, but still large. There is much to study. For the purposes of this performance and its place in our series, there are three other items which should be mentioned, however quickly, to explain its presence:

- The strange end of old Vienna has something to do with the beauty of this symphony.

- This is an arrangement of an enormous work. But this reworking doesn’t so much count as a ‘reduction’ — ‘study’ is probably a better word. The arrangement is based on one made by students of Schoenberg in the 19-teens who admired Mahler. Reducing the necessary forces lies somewhere between ‘copying’ (we must remember the ‘copyists’, who would copy out parts for players), and making a piano version, through which symphonies could be encountered in private by readers of music. To actually hear the symphony would be rare. (There will more discussion of this around the Eroica symphony to take place on Sunday.)

- This year marks the death of Claudio Abbado, with whom both directors have worked substantially — not least in the making of a Mahler symphony cycle at the Lucerne Festival in Switzerland over the past ten years. Maestro Abbado’s life was one of remarkable influence and achievement, giving direction and possibility to generations of younger musicians, and leaving a long legacy of performance and recordings. He is missed in the world, and we wish him the best in whatever worlds there may be to come.