Since his death in 1791, Mozart has had a lot of afterlives. He is still the mascot of Austria, still ruling in Salzburg and battling for control of Vienna. He is the prodigy against whom all prodigies are measured. He is the key to infant brain development. He fights crime outside of 7-Eleven. He helps plants grow. He helps cows make sweeter milk. He flies into space. He is a vast industry. He is Western culture. He is world culture. He is human possibility. He is everywhere, he is genius.

It’s a lot for a dead man to live up to. But even for the darkest skeptic (Glenn Gould, for example) some things must be hard to deny. The fluency — such an intensity of descriptive language in musical form — can make one doubt that musical forms are synthetic. One forgets that musical composition might be troublesome, that solutions to its technical and emotional issues are not always at hand.

It’s a lot for a dead man to live up to. But even for the darkest skeptic (Glenn Gould, for example) some things must be hard to deny. The fluency — such an intensity of descriptive language in musical form — can make one doubt that musical forms are synthetic. One forgets that musical composition might be troublesome, that solutions to its technical and emotional issues are not always at hand.

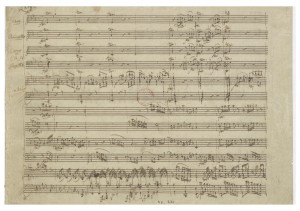

And though tales of his manuscripts’ perfection may be exaggerated, they are still uncannily clean. Above, for example, is an image of the first page of the manuscript of the wind quintet. The quality of deep organisation is already clear. The motions and developments move doubtlessly through the instruments. The wind quintet has this quality of uncanny ease, of difficulties encountered as opportunities, of imbalances leveraged for greater balance. Mozart knew this well enough when he wrote it, saying simply (in a letter to his father after its premiere), “I myself consider it to be the best thing I have written in my life.” Maybe it’s not as good as things he wrote later, but still good enough. Maybe not heavenly, but good enough for Earth. Maybe not eternal, but good enough to play again this year, to hear what all the fuss has been about.