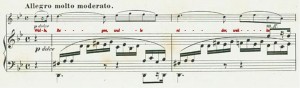

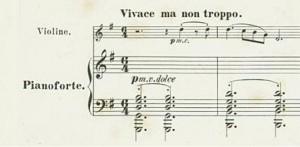

The beginning of the last movement of Brahms’ Sonata for Piano and Violin No. 1, Op. 78, is the same as that of his ‘Regenlied’, Op. 59. One can even safely say, given the totality of the song quotation, that this Sonata is ‘about’ rain. If one knows the words, one can sing along a bit with the violin:

But then it stops. Halfway into the second line of text, it’s not the same song anymore. What should have been a rather specific specific turn toward nostalgia:

Walle, Regen, walle nieder,

Wecke mir die Träume wieder,

Die ich in der Kindheit träumte,

Wenn das Naß im Sande schäumte!Pour, rain, pour down,

Awaken again in me those dreams

That I dreamt in childhood,

When the wetness foamed in the sand!

is truncated, but made stronger:

Pour, rain, pour down,

Awaken…

And what is awakened, but not named, awakes and becomes the movement for violin. Something songlike that is not a song, something to do with rain, perhaps.

Although there is no indication of what was written first, it seems logical that the last movement is the basic source of material for the piece. (One can say beyond reasonable doubt that the first few bars of the last movement were written before, because they had been in the song for seven or eight years already.)

Although there is no indication of what was written first, it seems logical that the last movement is the basic source of material for the piece. (One can say beyond reasonable doubt that the first few bars of the last movement were written before, because they had been in the song for seven or eight years already.)

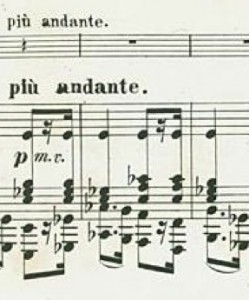

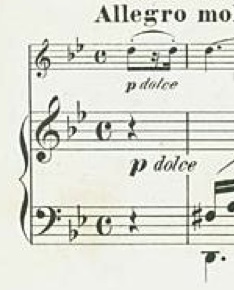

The overall feeling of the sonata is unusually cyclic and consistent. The halting-forward pickup rhythm which falls in the last movement also opens the first,  and appears in a brooding piú andante intermezzo during the second movement. These inter-movement connections are not puzzles, enigmas or parlour tricks. They bring a very affecting consistency of material and mood.

and appears in a brooding piú andante intermezzo during the second movement. These inter-movement connections are not puzzles, enigmas or parlour tricks. They bring a very affecting consistency of material and mood.

‘Affecting’ is an odd word, maybe a bit affected for describing a piece like this. This work is extraordinarily beautiful. The simultaneous presence and absence of words leaves space for imagining, space for notes to act a bit like rain, but also just like notes. Rain or no rain, a sense of natural motion is unusually strong. It was written in southern Austria in 1878, sixty years after Schubert’s A Major Sonata, fourteen before Mahler’s Das himmlische Leben, and twenty-one before Mahler’s Fourth Symphony.

‘Affecting’ is an odd word, maybe a bit affected for describing a piece like this. This work is extraordinarily beautiful. The simultaneous presence and absence of words leaves space for imagining, space for notes to act a bit like rain, but also just like notes. Rain or no rain, a sense of natural motion is unusually strong. It was written in southern Austria in 1878, sixty years after Schubert’s A Major Sonata, fourteen before Mahler’s Das himmlische Leben, and twenty-one before Mahler’s Fourth Symphony.